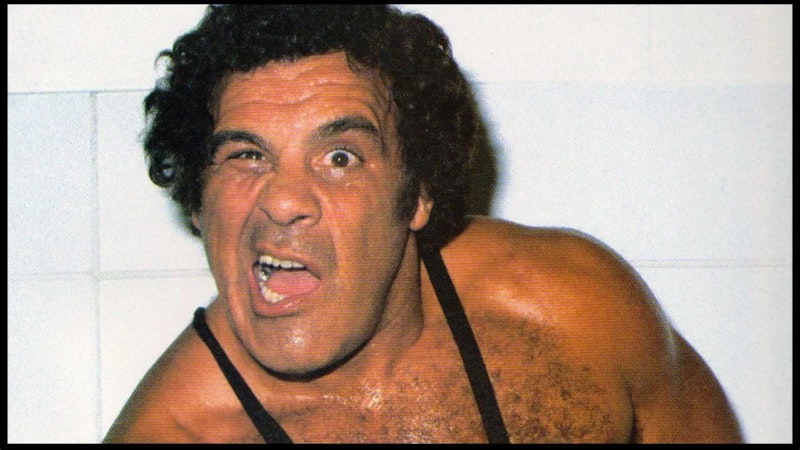

On July 8th of 1983, Angelo Mosca stood in one corner of Nassau Stadium’s infamously rigid wrestling ring. The meaty shoulders of his 6’4” frame carried the physical weight of the Bahamas Heavyweight Wrestling Championship, along with the much heavier psychological burden of a secret that he’d kept locked inside for several decades. As the mammoth brown-skinned Italian awaited the arrival of his opponent—the very charismatic, very white “American Dream” Dusty Rhodes—from beneath the chicken-wire structure that framed the pathway to the ring, we have to wonder if he appreciated the peculiarity of his situation.

There Mosca stood, in an island nation that was notorious for its support of Black wrestlers and its violent rejection of all who opposed them. In the main event of a wrestling program that kicked off the 10th anniversary of Bahamian independence—an event in which the Bahamians threw off the final lingering shackles of overseas imperial governance—the fans anxiously awaited the sight of Rhodes, the embodiment of American blue-eyed soul, and prayed that he’d climb into the ring and kick the Black guy’s ass.

Until the release of Mosca’s autobiography Tell Me To My Face in September of 2011, most people were unaware that the face they were metaphorically telling it to was—by many definitions—a Black face. In the opening pages of his book, Mosca unveils his secret racial identity with great reluctance, as he had only recently mustered up the courage to finally disclose the secret of his Black ancestry to his own family members after he’d turned 70 years old.

“It’s very hard to go your entire life lying,” wrote Mosca. “It may not be a lie of commission, but it certainly was a lie by omission. I just couldn’t tell people about it, because I’d been so drilled not to. My mother and father made me feel ashamed of my heritage and myself. I had it worked out in my head that Blacks weren’t accepted, so I wanted to only be an Italian. I had this secret inside of me and couldn’t let it out because I was scared of how my reality might change.”

In many ways, the juxtaposition of Mosca with Rhodes encapsulated several paradoxical questions of racial orientation. Can Black achievements be celebrated if their detection was intentionally obscured by the very individuals who accomplished them? Honestly, it’s impossible to properly evaluate the significance of Angelo Mosca’s revelation that he was significantly Black without also analyzing the complexity of what constitutes a Black achievement in professional wrestling. It can be heavily nuanced, and especially when it comes to the question of who gets to be an authentically Black wrestler. This is especially true when it comes to the matter of retroactive Black achievement in an era where anachronistic one-drop-rule hypodescent formulas are still rigidly applied by non-Blacks in some instances, and are self-imposed in others.

Archaic, unenlightened formulations of race devoid of considerations pertaining to organic cultural development have promulgated some curious contrivances. Consider that a person with 25 percent Native-American DNA could be denied affiliation in a tribe they rightfully descend from because they don’t reach the blood quantum threshold. Then consider that the exact same person could be defined as wholly Black if it could be proven that they had a single great-great-great-great grandparent of traceable African ancestry.

By this logic, some would enthusiastically claim The Ultimate Warrior to be the first Black WWE World Heavyweight Champion if it could be proven that Jim Hellwig had a tiny shred of African DNA. While the idea of Hellwig as a Black wrestling icon is uniquely humorous, the debate into who qualifies as a Black world wrestling champion is the perfect place to observe how sophisticated the question of Blackness can be when applied thoughtfully.

While many wrestling fans might contend that Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson broke new ground by winning the WWE World Heavyweight Championship for the first time in 1998, other well-meaning fans have questioned the historical potency of the accomplishment. Since Dwayne is both Black and Samoan, they reason, could he also have rightly claimed to have been the first identifiably Samoan world champion in WWE history if that barrier hadn’t been broken by Rodney “Yokozuna” Anoa’i? Does Dwayne’s multiracial makeup allow him to simultaneously chalk up victories in two racial categories? If so, is that fair to those who never get granted the option to pick and choose their racial identity when asked the question, “What are you?” because the answer is both glaring and unmistakable?

It doesn’t stop there. An additional complication is added to the debate when the “African-American” title is applied. In several circles, it’s a term granted conservatively to identify the descendants of African slaves who endured the yoke of slavery specifically in the United States. For some people, an additional requirement is imposed necessitating that a person’s ancestors remained in the United States and suffered the complications of the pre-Civil Rights era.

When the latter condition is applied, Dwayne isn’t only disqualified from achieving a full breakthrough for anything Black, but his descent from “Soulman” Rocky Johnson—an Afro-Canadian—prohibits him from breaking any ground on behalf of African-Americans as well. So it goes that the significance of Black milestones in wrestling has been relentlessly scrutinized. Were the world title victories of Kofi Kingston and Ettore “Big E” Ewen—a Ghana native raised in the U.S. and an American-born son of Afro-Caribbean immigrants—authentic African-American achievements? Should anyone care one way or another?

This brings us to Angelo Mosca, a mountain of a man who employs a dated analogy from the original Punch-Out!! arcade game—looked a lot more like Mr. Sandman than Pizza Pasta. By his own late-in-life admission, Mosca was born in 1937 to a white father and a half-Black mother in Waltham, Massachusetts. Mosca identified himself as precisely one-quarter Black, but with the caveat that the household in which he was raised on the outskirts of Boston accommodated no shades of gray… or brown.

“My dad made me feel embarrassed and ashamed about my heritage, so I hid it,” stated Mosca. “He looked at me like I was a little piece of crap. He yelled at me and screamed at me. Right from the earliest times, I can remember him smashing me, cracking me with his belt, kicking me, and calling me a ‘little black son of a bitch… He was the most prejudiced human being I ever met in my life.”

The extent to which Mosca’s decision to pass as white wasn’t driven by some semblance of survival necessity is debatable. His blackness was masked by the thoroughly Italian name of Angelo Valentine Mosca; he didn’t even need to whittle it down from a Black-sounding name like D’Angelo.

To his credit, the future Canadian Football League hall-of-famer took pains to share the conscious part of the thought process that drove him to reject his Black identity and present himself to the world as 100 percent Italian when his distance from his hometown family permitted him to do so.

“Today, being one-quarter Black might not seem like something to hide, but at the time, being the offspring of a mixed-race couple could be a curse. And it usually was,” continued Mosca. “My mother had many of the features of a Black woman, and if you look at me closely, I have some features people would consider African American, mostly in the nose. It’s broader in spots. Other than that, I don’t really show many Black features. My skin is dark and smooth, but that’s true of many Italians, too.“

Mosca’s upbringing was one of physical abuse from his father, and frequent racial epithets from his classmates that continued up until his departure from the East Coast to play college football in the Midwest.

“It was in third grade or so when I first heard someone call me ‘nigger’ but I just ignored it then,” recalled Mosca. “When I was a few years older, I started discovering the Black-White divide and the hatred that was everywhere in those days. A few classmates even started shouting ‘Hey Blackie!’ at me. Students made accusations about my being Black all through my high school years, but I never participated when other kids would show their prejudice against African Americans. Thankfully, teachers and sports writers never made mention of my race.“

After escaping from the Boston area, Mosca played football for Notre Dame University, but lost his scholarship when he got married, which was a violation of his scholarship agreement. He then joined the football program of the University of Wyoming, but never played a single down of competitive football for them as he “started doing all kinds of illegal stuff.”

Mosca eventually got arrested for stealing typewriters, for which he received a one-year suspended jail sentence. Upon being turned loose, Mosca almost immediately signed with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League. In the CFL, Mosca became an unqualified legend as one of the most dominant defensive tackles of his era. Ironically, one of the defining moments of Mosca’s football career centered around a borderline hit he administered to William Fleming, the Black star running back of the BC Lions. The hit was delivered just after Fleming was tackled close to the sideline during the 1963 Grey Cup Championship Game.

With Fleming knocked out of the game as a result of the hit, Mosca’s Tiger-Cats went on to win the league championship. Replays of the controversial tackle give it the appearance of being an innocent mishap in which Mosca had already committed to the tackle before Fleming hit the turf. Regardless, it was this play against a Black star football player that would fuel Mosca’s reputation for being a dirty competitor, ultimately leading to him completing his transition into a reviled pro wrestling heel.

Mosca had begun wrestling as early as 1960, but his off-season wrestling career picked up steam in 1969, with some Canadian newspapers labeling Mosca as “the man who helped prematurely end BC Lions’ Willie Fleming’s career” during their pre-match coverage of his appearances.

As Mosca’s football career ended and his professional wrestling career blossomed, Mosca did plenty of winning, and this is where the murkiness of his racial identity can obscure our comprehension of title histories. Depending on your personal practices for assigning racial labels to wrestlers, Mosca may have been the first Black holder of the AWA British Empire Championship, the NWA Canadian Heavyweight Championship, the Stampede Wrestling North American Heavyweight Championship, and perhaps most significantly, the title that would eventually become the WCW World Television Championship.

Then again, maybe he wasn’t. Whether or not wrestling historians recognize Mosca is a Black holder of any of the aforementioned titles is akin to college football programs choosing to recognize themselves as national champions prior to the 1950s; sometimes the fans claimed—and continue to claim—championships and distinctions that the schools simply do not.

Then there was that nickname. In 1977, Mosca fully leaned into the use of “King Kong” as his in-ring moniker. Even in the 1970s, when it was common to use racial signifiers to unmistakably identify the race or ethnicity of a wrestler, most wrestling promoters would’ve avoided equating a Black wrestler with earth’s most famous fictitious gorilla. The fact that Mosca’s refusal to identify as Black probably granted him unique latitude with respect to naming conventions is undeniable. Whether it was for better or worse is subject to debate. However, if Mosca had been open about his Black identity, then it’s unlikely that he ever would have been promoted under that name.

In a sports-entertainment era where non-stereotype-laden portrayals of Black wrestlers were few and far between, it might be bizarrely refreshing to classify Mosca as a Black performer who was known for his unrivaled toughness and superlative professional football career… if only such a retrospective analysis could ignore the fact that he is only afforded that sort of freedom now because he shunned such labels during the very era in which they would have mattered the most.

Since these are all talking points related to professional wrestling, there’s also the enduring question as to whether or not anyone should care about this. As former pro wrestler, wrestling agent, wrestling promoter, and wrestling trainer Steve Keirn has often stated, “This whole thing is a work. None of this is real. All the titles are gimmicks. They don’t really mean anything.”

For those who do care about such things, this brings us back to the Bahamas in July of 1983, when Mosca found himself holding a title that perfectly epitomized the symbolic quandary that his life decisions had placed him in. When Mosca was awarded the Bahamas title following a match against Rufus R. Jones—a bout that in all likelihood never actually took place—he defeated a very flamboyant and stereotypically Black wrestler. If nothing else, the Bahamian wrestling fans were led to believe that this is what had happened.

So it was that Mosca—a quarter-Black wrestler who ducked any public identification with Blackness—was positioned as a dominant white villain just so that he could lose the championship of a majority Black nation to Rhodes—a white, bleach-blond showman whose vocal intonations intentionally borrowed from the speech patterns of Black American evangelists.

For all intents and purposes, to the Bahamian wrestling fans in attendance, Rhodes was fundamentally Blacker than Mosca. And when Dusty Rhodes successfully captured the Bahamas title that day, he ostensibly struck a blow against white iniquity on behalf of the vocal Black fan base. Or, to oversimplify it to the point of absurdity, a white man took a championship away from a Black man in the name of Black sovereignty, and the Black fans who watched it happen enjoyed every second of it. Fortunately, Mosca came to terms with his racial identity long before he passed away in 2021, and the answers to any of his looming internal questions had long ago been supplied to his satisfaction. To wrestling historians and amateur sociologists, a host of questions remain.

How do you contextualize the Black accomplishments of a person who could’ve been Black and chose not to be? Should he be granted a pass because the circumstances of his upbringing caused him to view his Black existence as shameful? Should he be faulted for capitalizing on a lighter shade of skin that offered him a viable escape path from his traumatic life circumstances? If so, how much can he be blamed for leaning so heavily into an Italian identity that was also justifiably his by dint of birthright.

In several respects, these are the perfect questions to ask in a wrestling context, since the histories and authenticities of wrestling championships can oscillate between legitimacy and fraudulence depending on which wrestling fan you ask. In Mosca’s case, he bore the brunt of the beliefs about race that others imposed upon him, and he crafted a personal narrative until he decided that his racial identity was a truth that he could flee from no longer.

“I knew inside what I had in my background,” conceded Mosca. “You can’t change your heritage.”

Social scientists describe race as a social construct based on observable facts. If Mosca’s situation tells us anything, it’s that race and professional wrestling have a lot in common.